James Poro - East Islip Theatre

(This article originally appeared in Newsday Wednesday, April 10 1985)

The Italian immigrant boy named Giacomo Porreca, who was to become the American called James Poro, was barely 12 years old when he made his way alone from the village of Caserta, just north of Naples, to Providence, Rhode Island where his father was waiting for him. There was work in Providence, work making cement blocks with his father. But cement blocks and the three floor tenement at 129 Pasquale Ave were not what Giacomo Porreca had come to the New World for in 1898. He was ambitious, recalled his youngest sister, Rose Sinigalli, who still lives in Rhode Island, and he wanted to get ahead, which was, after all, what America was about for a young immigrant. Jimmy Poro was looking for something with more pizzazz than cement.

He found it in show business, which remained his romance for the rest of his life. And Jimmy Poro was served up a mighty large portion of life, having lived to be 98.

The love affair began when Poro was 14, and he hit the road with exactly 27 cents in his pocket. Shortly before he died in January, (1985) he told his youngest daughter, Kay Erwood, what had precipitated his departure from Providence. He was working at a fruit store with a friend when a stranger approached the two boys and asked where he could find a woman. “My father didn’t understand” Erwood said. “He thought he meant a date." But his friend was wiser in the ways of adults, and he told the man where he could find the kind of woman he was seeking. Young Jim was given the job of leading the stranger to a house of prostitution nearby. In return he got a $5 gold piece. Louis Porreca noticed the enormous wealth his son had suddenly accumulated. When Jim told how he had gotten it the result was a beating that bruised the boy's pride far more than his behind. Without a suitcase, Poro Just picked up and left.

Poro got as far as Newport, where he ate bananas for several days. Soon the pushy kid from Providence was an usher at the B.F. Keith nickelodeon in Pawtucket. The job included covering the seats in the theater with sheets after the show. Poro sang while he worked, and in the best show business tradition, he was overheard by the orchestra leader, who put him on stage. Next stop, New York. It was the turn of the century and vaudeville was king, so Jim became an entertainer. He was a small man, good looking, and always sharply dressed. As a singing waiter in North Beach (now the site of La Guardia Airport), he shared tunes and tips with a fellow named Irving Berlin, and on stage he went as far afield as the Glen Cove Opera House.

Poro told his daughter, Betty Speiss, that he was responsible for introducing Fanny Brice to her hit "Hi, Neighbor." but he also introduced some never-to-be-remembered tunes like "Over the Hill to the Poorhouse."

While Poro was doing his act in an Astoria theater, Johnny Horn, the pianist for the silent films, brought the young entertainer home for dinner. Katherine Horn was sitting on the porch embroidering that afternoon.

Poro not only charmed Katherine Johnny's sister, but charmed her Episcopalian family out of their objections to marrying an immigrant, and a catholic to boot. The couple and her family walked to the black stone Church of the Redeemer in Astoria on an icy January 9th 1912.

It was time to settle down. So Poro gave up his singing and traveling and went into talent and theater management. For the life of them, his family couldn't understand why Poro never sang again, not even for the family.

The immediate price of domesticity was a pay cut from $30 a day to $15. As it turned out, it was not a bad career change. Poro developed management skills that were legendary, as he would tell you himself. He once told a friend how he took over a failing Roxy house with 2,800 seats in Jamaica and managed, through his old connections, to get exclusives on some of the big films like “The Hunchback of Notre Dame”

He packed ‘em in. His son, Jim Jr., said that in the 20’s, when his father was managing several theatres in close proximity, he would hire “reel runners” to shuttle rolls of film by bicycle between houses. This way, several of the houses could play the same movie, and Poro had only to pay for it once.

The first Poro daughter, Gloria, was born 10 years after her parents' marriage. Then came Betty and the move to the suburbs, a rental in East Northport. Then came Jim Jr. and Kay and a house in Islip.

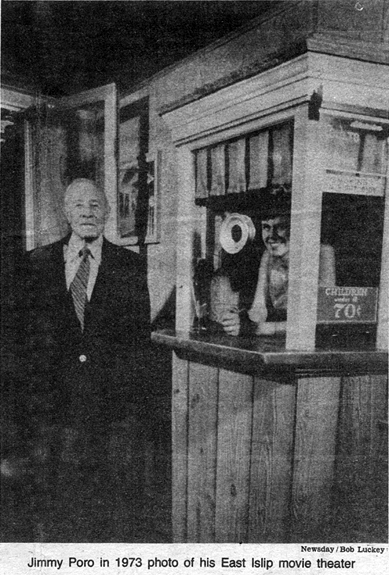

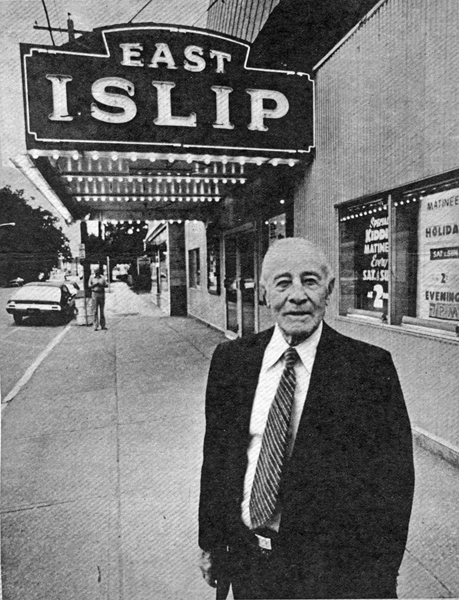

Poro opened theaters in Riverhead, Babylon and Sayville for a chain. Then he went out on his own, at various times owning movie houses in Hempstead, Mineola, Smithtown, Kings Park and Sayville. In 1932 he bought the East Islip Theater, which he kept for 42 years, holding out against the big chains, which might have outspent and out promoted Jim Poro, but could not possibly love their theaters the way he did.

He spoke of them always as theaters, not movies. And he came to work each night dressed in a shirt and tie, his cigarette in a holder. "The Count," Katie used to call him.

And almost every night after the show, he'd head to the old Bronco Charlie's in Oakdale and later to the Seascape Inn in Islip to pal around with friends, members of the East Islip Chamber of Commerce and the Lions Club of the Islips, both of which Poro helped found.

He stoked himself for his late night partying with his famous afternoon nap. It was not unusual for Jimmy Poro to close the Seascape down at an age when most of his contemporaries had already departed not only the Seascape but this world as well.

He was never the typical family man. The rearing of their four children was left to Katie, who died in 1963. When the children were growing up, Jim Jr. said, every Saturday night between shows his father would take his family to Cooper's Hotel in Bay Shore for dinner. "That was the extent of my mother's social life." The children remember the year their father sent their mother a birthday card signed "James Poro." I don't think she spoke to him for months." Jim Jr. said.

Their arguments were legend. She used to throw pots and pans at him," Jim Jr. said. "But she loved him dearly." He didn't philander, and, between the movies and his side work in real estate, he was what was called in those days "a good provider.”

He was also a master promoter. He held free dish nights, where each week the patrons got another piece of china and the sound of plates accidentally dropping to the floor punctuated the soundtracks. He held cash drawings, and the winner had to be present. He installed a TV room in the Sayville Playhouse, so husband’s could watch sports while their wives saw the movies. And he kept his properties spiffy. His son, now a bank executive who worked for his father for a time, said, "He was a tyrant. I wouldn’t work for him if he wasn't my father."

Before television, theaters would often show films of fights in addition to movies. The fight films, as the story goes, were distributed by men linked with organized crime. Poro had a habit of renting a fight film for one theater and showing it in two. One day a “Distribution Executive” discovered a film playing in the wrong theater. Industry people tell this story: Poro was visited by a distribution executive-cum-mobster, who ordered Poro to atone by giving a $10,000 donation to his parish priest. The next morning the "executive" went to Poro's office and watched the priest accept the donation. After the Father left the office, a third person approached him and mentioned how happy the priest must be with the donation. "Father? Who's a father?" the priest is said to have responded. "I'm a janitor in one of Jimmy's theaters. He rented me the outfit." Poro always insisted that he didn't quite remember that episode, but Kay thinks it is right in character. "My father thought he could get away with anything, and he usually did."

But never let it be said that Jimmy Poro didn't have his soft side. The retired actors at The Percy Williams Home and the orphans at Brookwood Hall, both near the theater, and the priests and nuns from St. Mary's church next door were invited in free. When the church burned down, Poro let the priests say mass in the theater, although he did open the candy stand to catch the parishioners on their way out.

All this didn't help when Poro showed "I Am a Camera," which dealt with virginity, abortion and menstruation, subjects that in 1955 were taboo. The church members picketed. Kay said her father got a friend with a camera to take pictures of the protesters, which scared the daylights out of them and dispersed the pickets.

Despite the dish and drawing promotions, from the '50s on movie houses were in trouble. First it was competition from television, then a shortage of films and then the big chains. Jimmy Poro fought back. He would buy property in a village where the chains were interested in building, said his son, and "he'd put a foundation up with no thought of putting in a theater at all. He'd wait until they [a chain] got word- they'd come and buy the property for twice what he paid. He'd just like to beat out the big guys. Maybe because he didn't build up a chain himself. The most he ever had at once was three theaters, and he wanted 300."

He was never to become come of the industry's moguls, but he clung to the edges of show business until the day he signed away the deed on the East Islip (Theatre) in 1974. He was 88. By the time he retired, his longevity alone was reason for celebrity. On his 90th birthday, a small party planned by the Lions turned into a formal bash for more than 100, at which he said, "If I'd have known I was going to live so long, I would have taken better care of myself." That year, he went to the Waldorf Astoria to be honored by the Movie Picture Pioneers. In 1983, at 96, he rode in the lead car as grand marshal of the Islip Tercentenary parade.

And almost to the end, he could be found at the Seascape with the boys.

When his body started to fail him and he could no longer live alone in his house in Islip, his children suggested a nursing home. He didn't even put up a fight. He lived in the institution for a little more than a year and finally just stopped eating. He died of pneumonia Jan. 13. Kay said Jim Poro told his children, “This ain't no fun anymore. I want to let go.”