Double Diamond Anniversary

Brookwood Child Care

Founded 1833 as the

Orphan Asylum Society of the City of Brooklyn

The First 150 Years - Part 1

On Friday, May 17, in the third month of Andrew Jackson's second term as President of the United States, a group of concerned women and their "gentlemen" advisers, all prominent residents of the Village of Brooklyn in the Town Of Brooklyn, (1) met at St. Ann's Episcopal Church on the Heights where they adopted a 12-article constitution for a new charitable enterprise that they called, temporarily, "The Brooklyn Orphan Asylum Society."

Eleven months later, on April 18, 1834, they must have been delighted to rename it the "Orphan Asylum Society in the City of Brooklyn" when their fast-growing community of 20,000 people with its excellent harbor and the two ferry lines that linked it to nearby Manhattan became a municipality in its own right, having finally -and in spite of opposition from the "big city" across the river -obtained a charter from the New York State Legislature. (2)

Curiously, the day of the month of that first public meeting at St. Ann's is not recorded in the one surviving printed copy of its first annual report (for the fiscal year ended May 24,1834). The accepted May 17 date seems to have been supplied years later by people who were present that day.

Nor is there any record of exactly how many citizens attended, although it's reasonable to suppose that most, if not all, of the 39 women who would serve on the first Board of Managers were on hand, as were the seven men, including two judges and two lawyers, who would make up the first Board of Advisors and who, together with the Rev. Dr. Cutler of St. Ann's, had helped draft the constitution and would later help write the by-laws and the asylum rules. (3)

In his comprehensive "History of the City of Brooklyn," published in 1870 when many of the principals were still living, Henry M. Stiles attributes the "idea of forming an association" to Mrs. Elizabeth R. Davison, who was deeply worried about children left parentless "by the ravages of the cholera in 1832." Contemporary accounts, however, suggest that Mrs. Joshua Sands, (4) who was certainly among the Society's leading proponents, along with other activist colleagues, was equally instrumental in its establishment.

Whoever the innovators may have been, though, it's clear that the project had an astonishing amount of community support from the Outset. (5) The first report lists 188 "annual subscribers," or members, the managers among them, who made gifts of $1.00 to $10.00, five "life members" who gave $25.00 each and 40 other supporters whose donations included "a widow's mite" of 13 cents, 25 cents from "a poor French woman" and a munificent $50.00 from George Hall who had become the city's first Mayor in May, 1834.

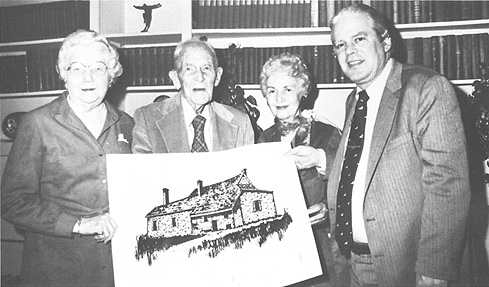

The late Francis E Walton, Honorary Historian, examines sketch of First Brooklyn Orphan Asylum with fellow Society members, Mrs. R. Whitney Gosnell, left, former President; Mrs. John Jay Wittmer former Recording Secretary and Bruce H. Wittmer current President. Mr. Walton, who was 100 years old on May 17, 1983, had been associated with the Society for 56 years as a member of the Advisory Board and Treasurer. He died in June, 1983

2

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Looking back with the corrected vision of hindsight, the public support that seemed so astonishing to a later generation was a logical enough development, considering the era and the prevailing social and political conditions.

In the 1830's, America and, particularly, the cities in the Northeast were just beginning to feel the impact of the Industrial Revolution with all of its attendant blessings and evils. The opening of the Erie Canal in 1825, giving ready access to raw materials from the West and thereby greatly accelerating trade and manufacturing, made New York the biggest city in the country. Neighboring Brooklyn, profiting from the business overflow, expanded at an even swifter rate.

At the same time, the new factories and related industries, hungry for cheap labor, had a devastating effect on underprivileged adults and children, native-born and immigrant alike, forcing them to work brutally long hours under dreadful conditions at wages barely sufficient for their meager sustenance and the rental of squalid hovels. It's no historical accident that the first half of the century witnessed the birth of many of the great reform movements and the first hesitant steps towards the sharing of social responsibility.

Mrs. Ann Sands, a founder Portrait was painted when she was ninety.

Evidently, the Society's founders and friends were people closely attuned to the trends of their times and they responded with vigor and determination. It's noteworthy that, while cholera may have been a precipitating factor, the malady, as such, is not mentioned in the first report. Instead, a revelatory passage reads: "This Society was established ... to provide for the education and employment of orphans and destitute children. And will it not be admitted that Brooklyn then needed and still needs such an asylum? Is it not a painful truth that children are often left destitute of parents and placed in the abodes of vice and misery beyond the influence of virtuous example?"

In any event, following the May 17 meeting, Ann Sands prevailed on two sisters named Jackson to lend the Society a house they owned on Brooklyn Heights. Situated on Love Lane near the intersection of Willow and Pierrepont Streets, it was an old, two-story, low-pitched, Dutch-style "mansion" about 60 feet long, and was thought to have been used briefly as a wartime headquarters by General Washington. It was constructed of rough-hewn stone with a roof of scalloped wooden shingles. Its front faced the river and there was a vegetable garden in the back. Not much is known now about the interior arrangements except that the fireplaces were made of blue and white tiles, and there was ample room for the 14 boys and 12 girls who became its first residents, as well as for a matron and two or more servants. Before the youngsters could be admitted, however, the place had to be made habitable.

Consequently, over the summer and early fall of 1833, the managers, taking turns, worked hard to renovate, furnish and supply it. A recently-discovered ledger of receipts and disbursements between 1833 and 1854 shows initial outlays, commencing on July 16, 1833, for the book itself (88 cents) and for cleaning, wood, tin and furniture. The earliest indication of children in residence is an entry of $32.99 for groceries on October 17, Later in the year, there are entries for such homey things as soap, dry goods, crockery, shoes and hay to feed a cow do nated just before Christmas.

About the first children, only fragmentary information exists. (6) They were, apparently, between three and eight, and we know their names, but not always or in each case, their exact dates of birth, dates of admission and discharge and what eventually became of them. Eight, it seems, were orphans. The rest were children of "destitute widows who are enabled by their daily labor, to pay the small sum of 50 cents a week for their support."

3

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

One of the boys admitted in 1833 was Dominick McLaughlin, a motherless, badly crippled four year old, who spent 13 years in the asylum and thereafter earned his living selling newspapers and confections at the ferry terminal. He died in 1863, bequeathing his life savings of $572.93 to the Society and his crutches to the first returned Union Army soldier that might need them. Dominick had two slightly older sisters, also asylum residents. Mary Ann left in May, 1838, presumably taken in by a relative. Bridget had left earlier, in 1837, but in 1841 was "placed with" a John S. Doughty of Brooklyn. Two others in the initial group were eventually placed with families, quite likely "bound out" or indentured as servants or apprentices, inasmuch, as no adoptions, as such, were recorded before the 1840's. Another child, five-year-old Isabella Houston, died in April, 1834, when the late prevailing epidemic reached the Asylum and laid one of its happy little inmates in the grave."

All in all, the children appear to have been reasonably comfortable, comparatively healthy, decently clothed and, for the times, adequately nourished. They were required to get up at six o'clock in summer and seven in winter with "plentiful use of cold water ... and generally habits of cleanliness to be observed." Before breakfast of bread or mush and milk "when it could be had;' they assembled to hear the matron read a chapter from the Bible and a family prayer. Then, six days a week at nine o'clock, they would "attend their studies, according to their ages and abilities." Boys, as well as girls, were taught to knit and sew.

Dinner, served at half past twelve, consisted of "soup or baked beans, beef, mutton or veal, partly at the discretion of the matron, only stipulating that it shall be healthy and frugal:' Lessons were resumed at two o'clock and concluded at an unspecified hour with the singing of a hymn "when practicable." The evening meal was "much like breakfast The children went to bed at seven after hearing a final prayer offered by the Matron. Every week, after Sunday school, the older boys and girls were taken to services at one of several nearby churches. As the asylum became better known, the children were frequently invited to picnics, holiday dinners and other entertainments by church groups and local organizations.

Unfortunately, there are few records left of the asylum's early activities. If annual reports, then called "manuals," containing narrative material and financial statements were published between 1835 and 1844, as many surely were, they are now irretrievably lost, as are a smaller number printed between 1846 and 1862. From 1863 on, though, reports and many other important documents were preserved. Most of what's known about the Society during its first two decades or so comes from specific references in these later reports, especially those issued in major anniversary years.

Nevertheless, a fascinating, albeit incomplete, picture can be pieced together from the several sources available. In 1835, for example, we learn from an 1883 historical sketch, "the state of the treasury" didn't allow for the printing of a report, while the ledger shows that a recently-engaged cook named Margaret Martin was paid $7.00, seemingly for six weeks of work.

There's also an item of "5.00" for an ad in Spooner's paper," but its purpose isn't stated. (7) Expenditures for the year came to $1,029.41, an increase of $191.72 over the first year's total of $837.69.

In 1836, expenditures went up to $1,802.74, and a third anniversary observance was held in the Common Council Hall where "the children recited passages of Scripture, hymns and the multiplication table." By the beginning of the following year, with admission applications on the rise, the house on Love Lane was no longer considered adequate, and the managers decided they had to have their own home-even though free use of the Jackson place had been graciously continued after the property was sold a year or two earlier to Jonathan Trotter, an attorney and a subsequent mayor of Brooklyn.

A plentiful use of cold water to be

practised.

A plentiful use of cold water to be

practised.

4

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The new project was admittedly ambitious, but it got off to a fine start in August, 1838, when General Robert F. Manly, a friend, donated eight lots "out in the country" on Cumberland Street near Myrtle Avenue. Four of the lots were deeded "absolutely" and the other four on condition that they belong to the asylum as long as they were used by it. A building fund was established, contributions from "the citizens of Brooklyn" began to come in and the cornerstone was laid on October 10. Construction was completed in the spring of 1839, the work having been supervised by Adrian Van Sinderen, prominent attorney and long-time member of the Board of Advisors. The children moved in on June 10.

We have no detailed description of the Society's second home, and its over-all cost is no longer known, mainly because the pertinent records are missing. Later references, however, indicate that the building was "large," meaning that it would have been at least two stories high. It was built of stone, possibly granite, was well ventilated, had a basement and was surrounded by a fence with an iron gate. It could accommodate 130 children.

Between 1839 and 1845, nothing out of the ordinary seems to have happened. In January,1840, the managers bought a sheep for $5.00 and, in December, a coffin for $5.78. In 1841, they paid a first annual insurance premium, $28.00, to the Brooklyn Fire Insurance Company. A pig was purchased for $5.00 in 1842 and James Abraham was paid $17.25 for an unspecified number of coffins. The cost of coffins the next year was $12.00.

A copy of the printed report for 1845 still exists and it fills some of the gaps, at least by a inference. In it, Eliza R. Steele, Corresponding Secretary, comments on the Society's satisfaction with things, at one point stating: "This institution commenced with feeble means. It has no endowment, no patronage from the State; but yet the building has been paid for and the managers trust they have been gaining in influence as well as resources through the liberality of friends." Then, a little farther along, she suggests to potential contributors that "a suitable library would be a most valuable acquisition."

In that same year, the average number of children in residence went up to 45, with 28 admitted, nine bound out, two adopted and 23 returned to their parents. The rules hadn't changed much in 12 years. The word "bath" had been added to the stricture about plentiful use of cold water. Food was somewhat more varied with molasses now on the breakfast and sup per menus. Dinner on the Sabbath was limited to bread and butter, but on the other days the main course was beef or veal, pork and beans, pork, pot pie and corn beef. The youngsters were kept busy making some 96 garments. The boys also knitted 43 pairs of stockings and the girls made two bedspreads. A temperance society had been established and the Sunday school was "flourishing."

For the next five years, information is scanty. An act of the State Legislature in 1848 made the asylum eligible for a proportionate share of the money allocated to the public schools. During the period, yearly expenditures increased from $2,007.59 in 1846 to $5,615.68 in 1850.

According to the report for 1851, that year was one of "unvarying prosperity," and the treasury was "no longer exhausted." A "donation visit" to the asylum was arranged that autumn and "kind persons attended and poured in with liberal hand money, clothing, provisions, stationery and other gifts good and seasonable. "Thanksgiving and Christmas dinners were donated by the Sabbath schools of different churches. The managers of Greenwood Cemetery, through the good offices of Henry E. Pierpont, presented the Society with a plot of ground "where they may lay those of their youthful charges whom death may call away." Through John Jay, Esq., the asylum received a gift of $250.00 which represented a portion of the proceeds of a New York concert by Swedish singing star Jenny Lind, then starting out on her celebrated American tour.

The asylum's population at the end of the year was 143, and the house would have been overcrowded except for the new wing completed in May at a cost of $3,987.17. It, together with new play-house, was built on four lots contributed by John B. Graham, Esq., a friend, and John J. Halsey, Esq., a member of the Advisory Board.

The Society thrived during the 1850's, but by 1858, the year of its 25th anniversary, the physical plant needed "certain indispensable improvements." A laundry and boiler room were added, along with a larger kitchen oven. The dormitories were re-arranged and better ventilated, and gas for lighting was brought in, all at a cost of $1,000.00. The managers, anxious to make the house more comfortable "with some mode of generally warming it," wanted to put in a furnace, too, but funds for repairs were exhausted and the furnace was deferred until 1860 when a hot water system serving the entire household was installed.

The 1860 report shows that the institution was continuing to get an impressive amount of public recognition and support. That year, some 800 members and contributors gave over $2,500,

5

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Dominick McLaughlin left his life savings to the asylum.

Dominick McLaughlin left his life savings to the asylum.

mostly in small amounts. For the first time, too, the names of donors of tangible goods were published, and the quantities and types of things given by 126 thoughtful people were formidable.

Among them were boxes, cases, barrels, even wagon-loads, of fruits and vegetables, cookies, cakes and pies, jellies, preserves and condiments, hams, turkeys, pork and rounds of beef, coffee, tea, cream and sugar, flour, rice, cheese and herring, chicken salad, oysters and ice cream, soap, cologne and hair oil, dolls, writing paper and envelopes, books, flowers, and a pair of candelabra.

In the spring of 1861, with the onset of the Civil War, the managers "deemed it expedient to omit anniversary exercises on account of 'the painful excitement on the public mind arising from the unhappy state of the country! " They felt that the war would affect the asylum, but hoped that the "quickened sympathies of a heart-stricken community would prove even more noble to the call of charity."

They needn't have worried because, two years later at the height of the war, regular subscriptions and contributions stayed constant at the 1861 level and, in fact, a $5,000 legacy from the estate of John S. Wiley and a $200 contribution from "a group of gentlemen" for the erection of an asylum monument in Greenwood Cemetery made 1863 a very good year financially. In addition, "large donations of Provisions and Fancy Articles" were too numerous to mention individually, and the managers tendered "warmest thanks" by way of a note in the annual report. (8)

Society sent teenage boys to the "Great West.

Society sent teenage boys to the "Great West.

In 1864, after "persistent appeals" by the Children's Aid Society of New York, seven asylum boys were sent out to homes in the "Great West" where they were "cordially received and well treated. In some instances, they replaced sons of farm families who had been killed in battle. These Brooklyn orphans, tough street kids, mostly, were surprisingly happy in their bucolic environment, and many were adopted or simply stayed on informally when their periods of indenture expired. The practice of sending boys to the west continued for some 20-odd years and, ultimately, a total of about 150 went, although the numbers varied widely from year to year.

With the ending of the war in the spring of 1865, things returned to normal, although the evidence suggests that the Society, however much its members might have been affected personally, had itself suffered only marginal inconvenience. The report for the year notes that the annual fair and "donation party," suspended during hostilities, was held in December, this time "contrary to precedent" at the Academy of Music, then on Montague Street, and a total of $3,250 was raised in two days. The school room was refitted with new desks and seats but the need was felt for a larger playground and more space around the building.

Only a few years before, the asylum had been considered out of town. Now other structures were encroaching on it, and "the children have many temptations to truancy and worse faults from unavoidable contact with (other) children who roam the streets, climb the fences and hold intercourse, which has all the charms of lawlessness." Here, it turns out, the managers were leading up to something, and Mrs. J. G. Weld, the Corresponding Secretary, reveals what it was in a single straw-in-the wind-type sentence:

"Were a future removal deemed feasible and proper by those having such matters in charge, doubtless many advantages, both physical and moral, would accrue to the young inmates:' The Society, obviously, now that the war was over, could begin to think seriously about a third and much bigger home."

The 1865 report is also noteworthy because of a passage in it that seems to foreshadow mid-20th century social thinking. The managers were said to be concerned about "the prevalent idea that any one on application can have a child of any age, and that it is rather

6

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

a favor than otherwise to take one." "Not so!" they emphatically declared. "Our children are not lightly esteemed or surrendered. The claims and character of each applicant are carefully examined, and satisfactory evidence is required that children shall receive mental instruction, be taught good habits, be not overworked and be generally kindly cared for."

By the next year, the managers, perhaps ahead of their time once again, were urging upon our friends the necessity of sustaining liberally the great work of rescuing and training those who will, if neglected, fill our towns and cities with vagrants more numerous than now infest them: for early neglect is the school which fosters vicious habits, leading to ignoble lives-perhaps ignoble deaths."

They were troubled, too, about the problems of adolescent boys (but not, apparently, of girls) and they approached the subject with a certain Victorian delicacy. Mrs. Weld, still Corresponding Secretary, noting the "frequent and favorable accounts of indentured children:' concluded that they were "well started in the life of labor and self-reliance which is to be theirs." She added, "It is thought desirable to have the boys indentured or removed when they reach the age of twelve. They grow restless and mischievous and do not have bodily fatigue or exercise sufficient to balance the natural craving for excitement which belongs to their recission from childhood."

In the housekeeping department that year, "an additional bathroom was found necessary, and it was supplied." This is the first reference to such a facility, and a latter-day reader can only speculate on how many there were originally and how they were equipped. At that point, the population was 130, and the house was crowded, "too much so for the general health, and we daily feel the need for a larger building and more extensive grounds."

At the end of the following fiscal year, 1867, the house was still crowded with 138 youngsters in residence. Nevertheless, Mrs. Weld could report that the "yearly health has been excellent as the general appearance of the children testifies: adding that "two only have died." One was a girl of 12, "a sweet child," who had suffered from an unspecified but chronic disease. The other, a little girl of four, fell victim to the measles.

In the spring, the constitution and the by laws were amended, just as they had been from time to time since 1833. Most of the changes were in the areas of administration and operating procedure. One, though, the revision of Article XII is important because it provided for the creation of a 12-member executive committee to "make inquiry into the circumstances of children offered for admission and also inquire as to their condition after having been bound out."

Alexander H. Dana was a member of the Advisory Board and chief legal counsel for 50 years.

Alexander H. Dana was a member of the Advisory Board and chief legal counsel for 50 years.

This was a significant departure from established policy. For thirty years, a seven-member committee had passed on admissions and "the propriety of binding out," but had no mandate to do any sort of follow-up once children left the shelter of the asylum. Now committee members would be empowered to take a close look at their "relationships and prospects (so) that they may have any advantages due them and in seeing also that those indentured by the Society meet with the protection and justice promised them."

The managers, admittedly, had become aware of abuses in the indenture system and moved to correct them, especially those that affected older boys who, they decided, should be allowed "to work for themselves" before reaching legal age. "Some boys at eighteen," they said, "are almost if not quite men-and subordination to the will of another, not a parent, is slavery-crushing the spirit, abating self-respect and deadening the energy which one who owns himself and is self-dependent develops before the age of twenty-one, if he develops it at all."

The concern for the welfare of the older boys particularly indigent orphan boys that few people cared much about is a clear indication

7

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

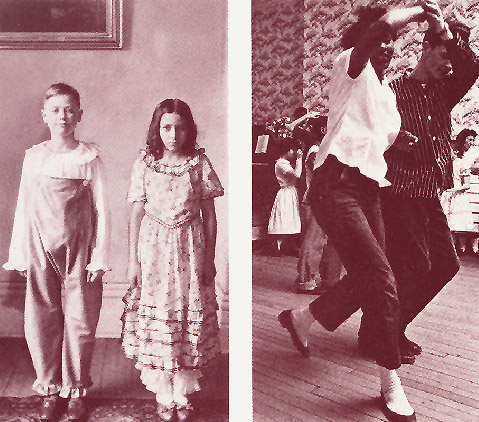

In 1933, kids model clothes of 1833. The Lindy- hop, Asylum-style, 1940.

of progressive thinking, although the managers' good intentions were undoubtedly reinforced by the prevailing public mood. The ending of the war, the imminent reunification of the country and the ratification, in December, 1865, of the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery nationally were causes for rejoicing in a Brooklyn whose populace had been fervidly anti-secession and anti-slavery. Then, too, the Rev. Henry Ward Beecher, the North's most celebrated preacher against the "peculiar institution," was an old friend and his Plymouth Church congregation contributed generously to the Society's work every year. At this juncture, then, anything smacking of involuntary servitude would have been anathema to the Society, as well as to the constituency it relied on for support.

The revised Article XII was something of a milestone in another way. Its last sentence, but one, which sounds almost as though it had been added as an afterthought, reads: "They (the members of the executive committee) shall also have general supervision and control of the Asylum under such directions as the Board of Managers shall prescribe and shall report at each monthly meeting of such Board." In effect, the new committee was the forerunner of the agency's present-day Board of Directors and it, together with standing committees created over the succeeding decades for specific purposes, gradually supplanted an increasingly unwieldy rotational system that required each manager, in turn, to visit the asylum weekly "to supervise the general household management, the health of the children and the course of instruction." The organization was still growing and now, in 1867, there were 61 managers, apart from the five officers, an 11-member Board of Advisors, 62 "honorary" members, 130 "life" members and 1,200 other contributors.

8

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Financial backing over the remaining years of the decade continued to grow apace, even though there was some apprehension about the "fearfully advanced rate of living" and wage increases for the matron, teachers and servants. Money raised at the annual fairs, however, together with donations through Church congregations, an ever-increasing number of legacies, payments received from the Board of Education, a share of the State's charitable fund and fees for children's board from certain parents and relatives were now approaching $40,000 a year

In fact, by the close of 1869, the Society was able to buy 47 lots at Atlantic and Kingston Avenues for $31,000. The purchase turned out to be a real bargain inasmuch as the property's estimated value, only two years later, had more than doubled to $65,000.

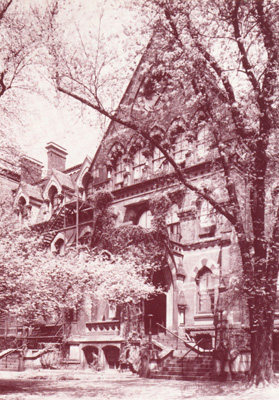

A special report on the progress of a new building, dated November 1, 1871, only 11 months after the laying of the cornerstone (9) and three months before completion of the major construction work, contains a description:

"The front on Atlantic Avenue is 187 feet, including the two wings (which are each 27 feet front (sic) by 80 feet deep), the main building being in depth 60 feet. The height of the whole is four stories, including the Mansard roof The basement story (which is above ground) is of blue granite. The rest of the exterior is of Philadelphia brick trimmed with Ohio and Connecticut stone. Special attention has been given to heating and ventilation. The front of the building is about 124 feet from the curb on Atlantic Avenue, and is about the center of the plot east and west."

There would be "much needed improvement" in the form of separate dormitories, classrooms and playgrounds for boys and girls. Provision was also made for grading and ornamenting the grounds, putting up fences, flagging the yard and sidewalks and for sewerage.

The building committee (10) that supervised the project had estimated that $60,000 was still needed to get the job done, and the Society used that figure to underline a bit waspishly, perhaps the fact that the State Legislature had promised to contribute $10,000 and to suggest that "an appropriation by the City Corporation would be eminently proper."

There is no subsequent evidence of response by the municipal authorities, but the general public must have agreed that "the Managers should be wholly relieved of any debt incurred by the new enterprise" because over the next and a half years all outstanding obligations had been paid and the only encumbrance against the property was a city assessment of $5,000.

Ultimately, the cost of the building and grounds was about $200,000, of which amount $27,500 was realized from the sale of the Cumberland Street building and grounds," (11) $10,000 came from the State and the balance from special gifts and bequests.

No. 1435 Atlantic Avenue.

No. 1435 Atlantic Avenue.

The children, all 135 of them, moved into their "elegant and commodious" new home on June 15, 1872. The formal opening ceremony took place two days later, the Rev. Beecher and two other prominent clergymen presiding. The children provided "interesting exercises" and, although we don't know exactly what they were, we can assume that singing, reciting and exhibits of sewing and handicrafts were included. For adult guests there was "ample provision for the inner man."

After the move to Atlantic Avenue, the asylum's population expanded rapidly, reaching a high point of 367 in 1882. Once again, facilities were overburdened and complaints were heard about lack of room for the many daytime activities that had been added to the basic program over the years. There seems to have been no question of creating more space through new construction so soon after a major building campaign, but two epidemics, one in 1876 and another in 1883, led the first "vision;' in 1885, of a hospital on the grounds.

During the seventies and eighties, the Asylum flourished. It was a time of accelerating material progress in America. The war, at least in the North, had given singular impetus to the manufacturing and distribution of goods.

9

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

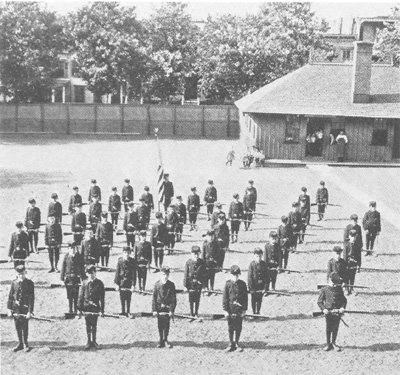

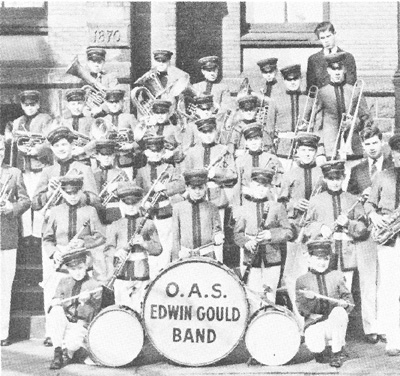

The cadets stay in formation. The band. The way it was in 1929.

Railroads were now criss-crossing the nation and, by 1890, would help erase the last frontier. American ingenuity seemed limitless, as invention after invention poured out of laboratory and workshop. In the two decades, in addition to the major industrial advances, the quality of every-day life was enhanced by a host of useful products, among them aspirin, carpet sweepers, cash registers, electric light bulbs, typewriters, lawn mowers, fountain pens and linoleum.

Advances in medicine were also notable. In 1873, the Society reported that four children had died of unspecified "diseases peculiar to young children," but by 1876, after being "visited by a severe type of measles" that left 44 children sick at one time;' a Dr. Pilcher, "made the operation of tracheotomy successfully three times, snatching the children from the very jaws of death." In 1885, an attending physicians' report appeared for the first time. In it, the diseases that had affected children during the year were named and their frequency stated. They included scarlet fever, German measles, erysipelas, malarial fever, rheumatism and locust-bark poisoning. There was a precise medical explanation for two deaths, one from pneumonia and the other from malignant erysipelas. In 1887, a new quarantine law slowed up admissions but helped prevent contagion.

In 1875, a small but significant change was made in the constitution. The nearby Industrial School Association had been doing similar work with distressed children. To curtail this duplicative effort, the Society negotiated a "distinctive" agreement under which the Association would accept destitute children with two parents, while the Asylum would serve only orphans and half-orphans.

During the period, while there was still great emphasis on religious observance and ways to keep youngsters busy during non-school hours, the atmosphere seems to have become a little more relaxed, and the children were getting out more, going places and doing things that were entertaining as well as educational. Horse-car service, inaugurated back in 1854, had been swiftly extended to all parts of the growing city. Two steam railroads, one to Canarsie, the other to Coney Island, had been built in the sixties and seventies. Soon after, six others, including the "Brooklyn and Jamaica" (later the "Long Island") reached outlying resort areas. These, along with the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge, in 1883, and the development of a network of elevated railway lines to move large numbers of people between Manhattan and the suburbs, made inexpensive-and rapid transportation accessible to everyone, including the Asylum youngsters.

Around that time, there were frequent references to outings and picnics in recently opened Prospect Park. There were longer trips to Coney Island, Rockaway Beach, far-off Speonk, and visits to private homes in Woodside, all courtesy of the railroad companies.

Although the children were undoubtedly having more fun, they were also getting more instruction in the practical things that would help them earn a living and, in the meantime, serve as a way of "banishing idleness and misdirected energy." A workshop was built on the grounds and a part-time instructor hired at $20 a month-to teach boys the use of simple carpenter's tools. For girls, a dolls' dressmaking department was created, together with a somewhat euphemistically-named "Kitchen Garden" to teach the "right way" to do housework. They wore aprons and little white caps.

10

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The manual training program was successful and, unexpectedly, profitable in a modest way. Two years after its inception in 1886, the boys earned $250 from the sale, mostly at the annual fair, of tennis, crab and fishnets, large and small hammocks and dolls' bedsteads. They also caned 485 chair seats. The girls earned a like amount; selling aprons, iron holders, bags and dolls' clothing. They also found time to darn 1,344 pairs of stockings. Later on, the boys would graduate to cabinet work and advanced types of carpentry, shoelace "tagging" and shoe repairing, which last, incidentally, saved the organization $500 a year. The girls added pillow cases, sheets, bibs and wash cloths to their list.

Together with the small annual fees paid by people to whom children had been indentured, a portion of the profits from the sale of handicrafts was set-aside for the young people's future. In one typical year, there was $2,600 on deposit in 61 separate accounts in the Dime Savings Bank and the Seaman's Bank.

While some of the managers still had mixed feelings about sending children to far-off places, most of the letters coming back to Brooklyn were enthusiastic. A boy named George was happy that another Asylum lad had been sent to a home only ten miles away, which he’d, visited "on horseback and in the wagon." He was also learning to chop wood. "We killed sixteen hogs this winter," he wrote, "and made jelly out of their feet and ears and helped make lots of sausage meat." Another boy who had "inherited vicious propensities found a home in the West, and Bennie's "new mother" wrote, proudly, that he was "energetic, truthful and honest."

The 50th anniversary, on May 17, 1883, was observed with little fanfare. An epidemic the previous summer that resulted in 11 deaths and kept four doctors busy tending as many as 65 sick youngsters at one time had dampened spirits. Too, an unusually large number of children had left the Asylum, including 18 adopted and 19 sent West, and the population was down to 281, a significant decrease. The decision had been made "not to extend the work, but to deepen and perfect it:' and the number of residents would thereafter be stabilized at the 300 level, only occasionally going as high as 325.

Between 1890 and the turn of the century, life on Atlantic Avenue was, by and large, serene and productive. Even the great measles epidemic of 1894 caused little alarm. No one died, and the hospital wing built ten years earlier easily accommodated the 96 afflicted youngsters. A telephone, installed in 1890, "despite the added expense" of $60 a year, also helped during what, in former times, would have been a calamitous visitation.

Oddly, the consolidation of Brooklyn with the other boroughs of Greater New York in January 1898, was not mentioned in the report for that year, nor was the Spanish American War, although 50 of the older boys enrolled in the "Elwell Cadets" would surely have done something special to mark the conflict. The cadet corps, named for James W. Elwell, a well-known attorney and a member of the advisory board who donated the uniforms and equipment, was formed in 1891 to give youngsters elementary training in military drill, as well as healthful outdoor exercise. It would be a much-admired and popular part of the Asylum program for the next 50 years.

Interestingly, in the last year of the old century, a large oil painting of Ann Sands was willed to the Society by her great grandson, Charles A. Sands of East Orange, New Jersey. The canvas painted shortly before she died in 1851, portrays an aged but alert-looking nonagenarian in an old-fashioned white bonnet. It still graces the Society's Brooklyn headquarters office.

The first year of the new century was remarkable, not for milestone-type predictions of growth and progress, as might have been expected, but for an "extraordinary" $8,000 repair bill. The building, due to age and constant wear and tear, needed extensive renovation inside and out, including major plumbing and lighting

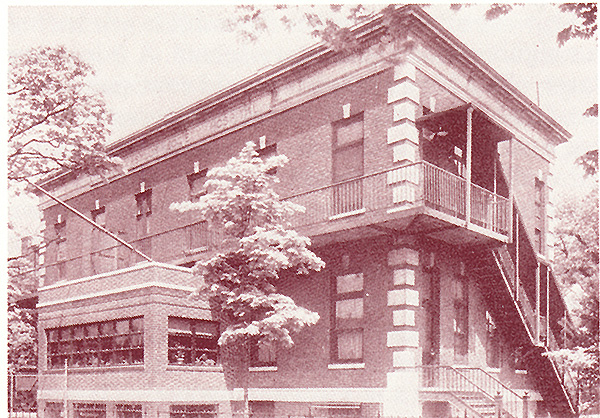

The "new" hospital was built in 1911

The "new" hospital was built in 1911

A quiet day in one of the wards,

A quiet day in one of the wards,

11

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

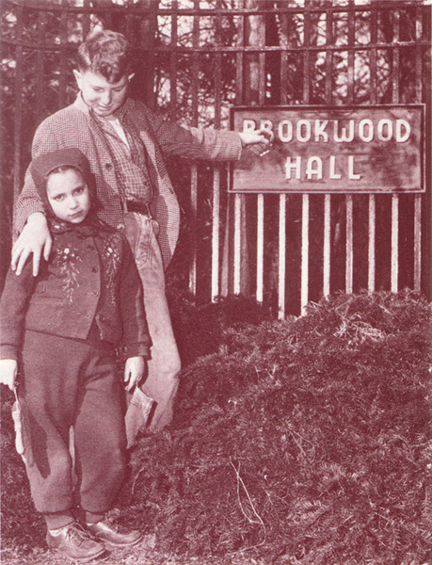

Brookwood Hall, East Islip, became the Society's fourth home in 1942.

changes and a costly re-slating of the roof. In addition, to comply with recent Fire Department regulations, an automatic alarm system connecting the Asylum with a nearby engine company had to be installed, and the main water supply pipe, by now irreparably rusted, had to be replaced. As it turned out, the cost of repairs and the replacement of furniture and equipment, while the amount varied from year to year, remained a substantial expense item until the building was finally sold 40 years later.

In 1900, the constitution was amended, once again, this time to provide for the creation of a 12-member "Investigating Committee" empowered to check on the references of applicants, visit the applicants themselves and look into cases of delinquent payment. Life was becoming more complex and, inevitably, more unprincipled. "Unpleasant as it is to know human nature in some of its phases," the managers asserted, "it has to be done and only in this manner, by direct contact, can we be sure of giving assistance with discretion."

The report for that year, perhaps in tacit recognition of the dawning era, was issued with a rather stylish gray-black cover that omitted the engraving of the first photograph of the building that had adorned every cover since 1874. Instead, an up-to-date picture appeared as a full-page frontispiece, and six more of the same size, reproduced by the new half-tone process, illustrated the text. These early photographs have an evocative, un-posed quality. They seem to have captured, touchingly, the essence of the time and the place: a dormitory with children in bed or kneeling in prayer; a corner in a hospital room with four small patients and their concerned adult attendants; the cadets in jaunty formation; girls absorbed in their needlework and boys busily mending shoes and caning chairs.

There weren't any pictures, then or later, of youngsters in their classrooms, but education was still a top priority, and the Society was quick to adapt to current advances in theory and practice. In 1903, for example, there was "a radical change" when 50 of the older children were enrolled in the "grammar grades" of a neighborhood elementary school. A few years later, older boys and girls would routinely go to academic and manual training classes in local high schools, and one youngster, breaking ground, would study art at Pratt Institute.

Starting in 1906, asylum teachers, like their counterparts in the public schools, had their hours shortened, their pay "equalized" and were given July off, as well as August, "an innovation that they appreciated," but which also raised a troublesome question: What to do with 300 lively boys and girls during such a lengthy period of free time? The "vexing problem" was solved a year or so later when the Board of Education sponsored, on Asylum grounds, an unprecedented summer playground program of sports, games, dramatics, music, dancing and handicrafts.

12

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Society could also take credit for "extending a helping hand" to retarded and "defective" children when it initiated, in 1910, an experimental class that soon developed into a weekly program to give as many as 24 children at a time the special training that "in former years was left to physicians and athletes."

Cultural horizons continued to expand during the early nineteen-hundreds. The motor vehicle, a novelty in 1903, was almost commonplace by 1913 when 175 Asylum boys and girls went by car to Coney Island, courtesy of the Long Island Automobile Club. The kids were going to Manhattan more often, too. Every spring, they went to Madison Square Garden, then at 23rd Street, to see the circus and, once, to a Buffalo Bill show. They attended services at historic Trinity Church, visited Ellis Island, marveled at the 42-story Singer Building and probably gaped at iron workers completing the upper floors of the even loftier Woolworth Building. The Panama Canal was much in the news in those days, and the children examined a scale model of it at Abraham and Straus. They went to Ebbetts Field a lot as guests of the Brooklyn baseball team, the "Superbas," later the Dodgers, and there was always something doing at the Academy of Music, in Prospect Park and at the Botanic Garden.

At home, the "family" celebrated its 75th anniversary in 1908 with a number of gala events, and had a set of commemorative dinner plates made in England by Plummer. In 1911, the new hospital, a handsome, two-story, redbrick structure, separate from the main building, "opened its welcoming doors." The following year, everyone mourned the death, on April 15, of an alumnus, a young man who went down on the Titanic.

The conflict in Europe raised "grave issues of the Old World" and, in 1915, the managers wanted the children to understand "that right, not might, is the glory of any nation." When the country went to war in April 1917, the asylum went, too, in spirit. The children participated in parades and rallies, and paid visits to Fort Hamilton and the Navy Yard. The Elwell Cadets won first prize in a drill competition sponsored by the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. The girls, working as a Red Cross auxiliary unit, made thousands of surgical dressings, doubtless hoping that their handiwork wouldn't be needed by any of the asylum "graduates" who were in the armed forces. (12)

The year 1918 brought peace to the nation and an accolade to the asylum. A District Superintendent of Schools, after an official visit, said the Society should be proud of its work and that "it is the best state aided school I have ever inspected." The following year, though, another far-reaching policy change occurred when the asylum officially became an annex of Public School 93, a development that saved a considerable amount of money in teacher salaries.

The postwar years were prosperous. While donations obtained through Protestant Church congregations had been gradually diminishing since the beginning of the century, other sources of revenue, both public and private, made up the difference. Legacies had become important around the middle of the previous century, and the money bequeathed was wisely transferred to an endowment fund, with only the interest on the principal used for operating funds. By the mid-twenties, the endowment-substantially increased by generous bequests in those prosperous times-was generating more income than any other revenue source. (13) Illustratively, church collections in 1909 amounted to $3,853 while invested endowment money produced $8,289. Twenty years later, the contrast was much sharper, with church receipts down to $817 and endowment income up to $76,206. People probably weren't attending services any less frequently, but the pattern of charitable giving seemed to be changing

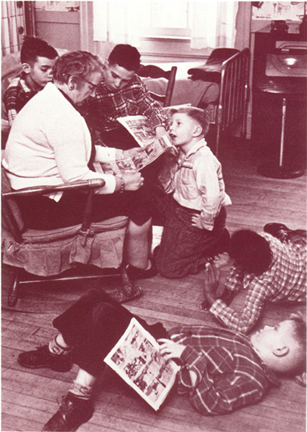

Relaxing on Sunday morning

13

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The high point in legacies received came in 1926 with a bequest of $250,200 from the estate of Charles E. Perkins. Two other large bequests in excess of $80,000, one in 1920 and the other in 1928, helped swell the endowment fund. During the period, the yearly fairs also did very well financially, with record receipts of $13,269 in 1927, including advertising revenue from the Annual Bell, the asylum paper published in connection with the fair since 1876, the country's centennial year.

Outdoor activities, especially during the summer, now accounted for most of the children's free time. Camping, something of an experiment in 1924 when a dozen or so boys spent two weeks at a lake near Bear Mountain, rapidly became a major program that, within a couple of years, would empty the Asylum in July and August.

During the other seasons, there were programs at the Y.M.C.A., which was liberal about providing memberships without charge, all kinds of sports (at one time there would be five baseball teams and basketball scores would be recorded in annual reports) and membership in asylum-sponsored Boy and Girl Scout troops. A band, initially composed of 15 boys and 15 girls, was formed in 1927. It was named after Edwin Gould, the noted philanthropist who would come to be called the Society's "most valued friend" because of the countless benefactions made during his lifetime and, by legacy, after his death in 1933.

On the whole, the depression years treated the asylum less harshly than otherwise. New legacies were scarcer, their amounts smaller and the interest from endowment fund investments declined to some extent. On the other hand, payments by the city for care and maintenance were up, reflecting the growing number of children referred by the Welfare Department, although the over-all population-as a matter of prudence-was kept down to about 200 at a time, a manageable number.

In a 1941 report, released after a general inspection-the first in five years-the State Board of Social Welfare complimented the Society on the fact that the children were well clothed and well fed. The inspectors also commented that "expenses have been held at a surprisingly even level ... and the amount from investment funds has held remarkably well."

The 1930's turned out to be a time of transition. By now, government was concerning itself, to an unprecedented degree, with the welfare of the individual. As a result, charity-at least charity of the kind that satisfied elemental human wants-was becoming more and more a partnership function between the private and public sectors. At the same time, the advances made in public health and medicine since the Civil War had reduced, year by year, the number of orphans needing shelter. Children, it was now widely recognized, needed help for many reasons other than loss of parents.

The junior girls' basketball team.

The Society, once again, reacted to new currents in American life. In 1935, it engaged a professional social worker who, in her first formal report to the board, was careful to point out that "our responsibility to the child does not end with giving him a happy environment, good physical care and educational opportunities." A year or so later, children were routinely being given psychological tests, and psychiatric treatment-a new-fangled notion at the time-was made available.

The Society was a hundred years old in 1933, and the centennial was celebrated in May with a gala pageant attended by a "large gathering of friends." Earlier in the year, an 80-page commemorative booklet had been published. In addition to a historical summary, it contained an invaluable store of details on the genealogy and the interrelationships of many of the key people associated with the organization over the years. Describing the role of the Dana family, for example, the report's author states, with obvious pride, that "in its hundred years, the Orphan Asylum has had but four legal advisors, all in one law firm and practically all in one family."

In December, 1941, the asylum went to war again. A defense program was speedily developed by the new executive director, the first person to hold the title. (14) It included blackout rules and procedures to be followed in case of an air raid. And, if the community needed it, the asylum was "ready and able to offer shelter and assistance to at least 150 additional adults and children. Another 75 people could be accommodated in the hospital, and there were beds, blankets and enough emergency food for two weeks.

14

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Fortunately for the community, it was never obliged to accept the offer which, in any case, would have been withdrawn in the fall of 1942 when the managers suddenly-or so it appeared -vacated the premises, putting most of the furniture and equipment in storage, and moved some 60 children-fewer than half the number of those in residence the year before-to a new home in the country. Almost simultaneously, the War Department, which had just rented the property to house Europe-bound Army units, moved in to make the necessary conversion.

While the actual physical transfer was carried out in a matter of ten hectic days, the decision that motivated it was by no means precipitous. For a long time the managers, now called directors, had been disturbed by the never-ending and ever-larger repair and renovation bills to patch up what had become, in 70 years, an antiquated building. They also firmly believed that city children would benefit greatly from a healthier and, certainly, different environment. Implicit, too, was the idea that the quality of service-given the same financial resources, could be measurably bettered if fewer children were involved.

So, in June 1941, having decided that a move was imperative, the Board put the property in the hands of real estate agents and formed a committee to search for a suitable site, preferably on Long Island.

They found their site the next summer near East Islip in Suffolk County in the form of a 52-acre estate "with beautiful lawns, trees, gardens, a large lake and suitable buildings." It was conveniently located 50 miles from New York City and easily accessible by automobile or the Long Island Rail Road. The Town of Islip had the requisite schools, churches and other amenities.

The children in the initial group adjusted readily to the semi-rural atmosphere, evidently not minding the inconvenience that extensive alterations must have caused. They went right to work planting the first of several Victory Gardens that would supply the household with fresh vegetables during the war and for many years afterwards. And they must have been looking forward eagerly to the skating, swimming, boating, fishing, picnics and the use of the playgrounds and athletic fields that the spacious grounds would soon make possible.

The new place was christened "Brookwood Hall " a name that linked the asylum's past urban association with its present countrified one. But the Society had never really left home. During the East Islip years, while children from Nassau and Suffolk were admitted, the largest contingent still came from the city.

In fact, after the war and because of the demographic changes caused by it, the number of deprived and dependent kids was greater than ever. Mostly, they were black and mixed race, "orphans of the living," that a future executive director would describe as "victims, once removed, of the intractable bigotry, brutal in difference and naive complacency that have brought our society to the point where the danger of violent explosion is very real." They were children who needed help just to grow up. The Society was prepared to give it.

In 1951, the Child Welfare League of America, the national standard-setting body, after making an in-depth survey, recommended the establishment of a foster care department. Fortuitously, the Society had moved its executive office to larger quarters in a brownstone house on Adelphi Street in Brooklyn's Fort Greene section a couple of years earlier. There would be space enough to accommodate the additional staff members that development of a major foster care effort would demand.

And demand it did, because the program expanded rapidly. The first child affected, a boy, was placed in a Nassau County home in late 1952. Twelve years later, there were 157 children in 69 licensed foster homes, mainly in Brooklyn and Queens. And as the primary service priority changed, income ratios changed with it. In 1963, payment for care of children at the residence was negligible compared to the $400,000 received from the city for the maintenance of children in foster homes.

The economic facts, alone, were compelling. Brookwood Hall was closed in the summer of 1964, and for the first time in 132 years, the Society had no large number of children to care for in one large place.

Cookies were on the house.

15

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

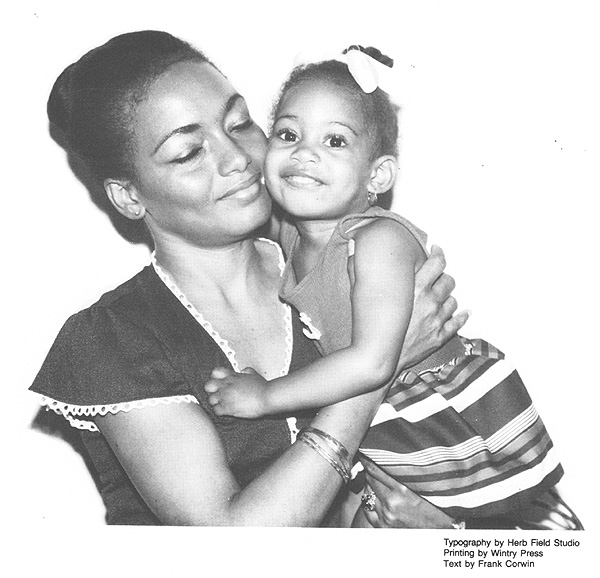

The way they looked in 1951.

Even the old name had been changed when the Board, in 1952, adopted the operational name, "Brookwood Child Care," because it was more descriptive of the work being done, although the original title was retained for legal and historical purposes. The organization itself, would thereafter be called an "agency," but the Society would remain the fundamental governing entity that would supply the members elected to the board of directors.

More than likely, many of those same Society members and directors shed a quiet nostalgic-tear or two when Brookwood Hall shut down for good. But they were committed to a promising new course of action and, as a former president" would later remark, they were more than willing, eager, in fact, "to discard the outmoded and the inadequate and take chances for children."

The concept of taking chances was to become a major determinant in policy-making, and during the ensuing 19 years the agency did a great deal of experimenting and "pioneering." Every innovative approach, of course, hasn't worked out, but in the few instances in which programs have been discontinued or curtailed, the causes have been due, usually, to circumstances beyond control, things like recession, cut-backs in public funds and political priority-switching.

For the most part, though, programs developed during the period have been singularly durable and productive, although some have been modified from time to time in keeping with community needs.

As a case in point, back in 1965, two group homes for teenagers were opened in middle-income rental housing. One apartment accommodated eight girls, the other eight boys, and they were used as an alternative to foster care for kids with special problems. A few years later, the two units were occupied by much younger children and they were called "family residences" because their biological parents, in a radical departure from customary practice, were made an integral part of the program and encouraged to become at least part-time parents. A couple of years ago, the situation changed and the homes serve teenagers once more, with the staff taking pains to get them through high school and prepare them for independent living once they leave the agency's protection.

In another instance, the Fort Greene Children's Harbor 24-bed group residence combined with 12-bed emergency care and diagnostic unit opened by the agency in 1976, was forced to close three years later when an unexpected fall-off in referrals resulted in a serious loss of revenue from the city.

The disappearance of the Harbor, however, wasn't a disaster because the neighborhood based service structure of which it had been the centerpiece remained largely intact. In one of the residual programs, parent-child counseling, the agency now works with hundreds of children and adults in families considered in danger of breakdown. Besides individual counseling, troubled parents get help with practical matters like home management and the development of parenting skills. The purpose is prevention of placement by keeping the family unit and intact.

The Harbor emergency care unit, too, was the forerunner of the agency's present complex of emergency foster boarding homes where children -as many as four at a time-can get immediate, though temporary, shelter in times of family disruption or in situations that threaten their health and safety. When the storm is over, they are returned home or, if the crisis persists, are placed in surrogate care.

The family day care program, also a preventive measure, is always oversubscribed because hard-pressed parents who want to work or go to school to learn a trade or a special skill must have a safe place to leave their young children during daytime hours. The care is given by "provider mothers" who make their homes available five days a week.

Adoption is a really bright spot in the service mix these days. The agency's specialized department now manages to arrange 30 or 40 legal adoptions a year, a very high number for

16

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

an agency of Brookwood's size. In the past, most of the children in need of permanent homes were black or racially mixed, and few were healthy infants. Lately, there are more babies and more white and Hispanic children available. Whatever trends develop, though, the agency has declared its intention to concentrate, in the immediate future, on finding suitable adoptive homes-and foster homes, as well-for kids with multiple physical and emotional handicaps. In doing that, Brookwood will be continuing its tradition of making a pragmatic response to the realities of need.

Today, in addition to their responsibility for conducting the major programs in foster care, adoption and prevention, board and staff members concern themselves with a number of less dramatic, perhaps, but equally indispensable things. Efforts to recruit new foster and adoptive parents are constantly made. Existing homes have to be monitored in compliance with state and city regulations. The families that accepted children have to be supported and encouraged and, when starting out, properly trained. Medical and dental problems are checked. The need for psychological help has to be determined. Clothing and other allowances in this inflationary period are frequently reviewed. Finally, in addition to internal administrative and personnel concerns, there is the seemingly endless paperwork generated by the various regulatory bodies to which a voluntary agency is accountable.

Putting it all together, Brookwood in 1983 is a thoroughly modern, non-sectarian, professionally-operated, multi-service agency well equipped for its primary mission: helping children in distress. In January, 1983, the Special Services for Children division of the Human Resources Administration rated Brookwood as one of the five "best" child welfare agencies in New York City, out of the 67 evaluated, and assigned it top priority for referrals of children by the public department. The rating was earned for excellence of program, general performance and adherence to established standards.

It seemed a good way to start the next 150 years.

17

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1. In 1833, a "village" in Kings county was the conventional cluster of dwellings, commercial establishments, public buildings and churches, but the "town" was a much larger geographical subdivision, rural or agricultural in character, with scattered hamlets. Besides "Breukelen" in the Northwest, the other original towns were Bushwick to the north and Flatlands, Flatbush, New Utrecht and Gravesend to the west and south. The 1834 charter united the village and the town and, by 1896, Brooklyn had annexed all of the adjacent areas, attaining its present area of 71 square miles.

2 . The Society was granted its own corporate charter by the New York State Legislature, and the "in" of its original title was changed to of giving the Society its present corporate.

3. The first Board of Managers was made up of Mrs. Charles Richards, First Directress; Mrs. Elizabeth R. Davison, Second Directress; Mrs. Sarah E. Austin, Treasurer; Miss Mary A Cunningham, Corresponding Secretary, and Miss Harriet A. Sands, Recording Secretary. The Board of Advisors included Mr. James Engles, Mr. Charles Hoyt, Judge Leftert Lefferts, Judge P. W. Radcliffe, Mr. Eliakim Raymond, Adrian Van Sinderen, Esq. and F. C. Tucker Esq.

4. Ann Sands, born Ann Ayscough in Salem, Mass., in 1761, was the daughter of a British Army surgeon stationed in the colonies and a mother of English and Dutch ancestry. Her husband, Joshua Sands, whom she married in 1779, became the first Collector of the Port of New York and a member of the House of Representatives.

5. Many notable people among the Society's organizers and friends are commemorated today by Brooklyn street names: Butler, Carroll Crosby, Doughty, Lefferts, Lewis, Mercein, Pierpont (later changed by the family to Pierrepont), Porter, Raymond, Sands, Spencer, Suydam, Talman, Taylor, Van Sinderen and Willoughby.

6. Children admitted in the fall of 1833 were Mary and Margaret Denny, Hester and Edward Gunn, Isabella and Samuel Houston, Charlotte and Mary Jane Long, Catherine McIntyre, Amos and Mary Augusta Ryder, Walter and Samuel Stanley, Mary and Catherine Wortman, Dominick, Mary Ann and Bridget McLaughlin, Edward Nathan and Francis Nugent.

7 . Alden Spooner, a transplanted New Englander, founded the Long Island Star in 1809. The paper, a four-page weekly, was strong on education and culture.

8. At the annual meeting on May 20, a resolution was adopted expressing sorrow at the death of Phoebe Butler, "the dearly-loved and deeply-honored First Directress of our Institution. " She had served since 1859.

9. Presiding at the December 1st ceremony were Rev. Beecher, Rev. Schenck and Brooklyn Mayor Kalbfleisch.

10. The members of the Building Committee, who were also members of the Advisory Board, were James W. Elwell, John Halsey, J B. Hutchinson, E. B. Litchfield, John W. Mason and James L. Morgan, Mr. Elwell supervised the construction and Mr. Mason took care of the financial arrangements. George Hawthorne was the architect

11. The building and adjacent property were sold to the Brooklyn Homeopathic Society. The site is now occupied by Cumberland Hospital.

12 . In June 1919, 25 of "our War Heroes" attended a festive welcome-home party at the asylum. A silent toast was proposed to the memory of five who had made "the supreme sacrifice."

13 . Later in the century the ratio changed. In fiscal 1983, agency expenditures totaled $2,291,557, of which $439,350 represented investment income. Public funds for "purchase of service" made up most of the balance.

14 . Francis M. Firth. The title replaced that of "Superintendent, " which had earlier replaced that of "Matron. " Succeeding Executive Directors were Jason S. Pettengill, 1944-1949; Frank F. Maloney, 1951-1963; John D. Lyman, Jr., 1963-1982, and, since January, 1983, Mrs. Betty C. Jones.

15 . Mrs. R. Whitney Gosnell in December, 1965. The title of "First-Directress" was changed to that of "President" in 1911. Since its founding the Society has had 19 presiding officers: Mrs. Charles H. Richards, 1833-1858; Mrs. Silas Butler, 1858-1863; Mrs. James L Morgan, 1863-1864, Mrs. John B. Hutchinson, 1864-1887, Mrs. Anna C. Field, 1887-1891; Mrs. George H. Nichols, 1891-1898; Mrs. James H Thorp, 1898-1899, Mrs. Michael Snow, 1899-1903; Mrs. James Truslow, 1903-1908, Mrs. George W. Mabie, 1908-1911; Mrs. J.R White, 1911-1912; Mrs. James S. Hollinshead, 1912-1917, Miss Sophie L. Meserole, 1917-1918; Mrs. August Dreyer, 1918-1926; Mrs. Anna E. Brader, 1926-1941; Mrs. Lucy M Houghton, 1941-1944; Mrs. Gladys M. Haman, 1944-1952; Mrs. Gosnell, 1952-1970, and since 1970, Mr. Bruce H. Wittmer.

Counseling at

Adelphi Street

Counseling at

Adelphi Street

OFFICERS (As of 1983)

Mr. Bruce H. Wittmer, President; Mrs. Paul B. Woodfin, II, First Vice President; Mr. Ellsworth G. Stanton, III, Second Vice President; Mrs. E. Onken Beery, Third Vice President; Mrs. William B. Falconer, Jr., Recording Secretary; Mrs. George M. Onken, Corresponding Secretary; Mr. Joseph J. Capra, Treasurer; Mr. Edward R. Hunt, Assistant Treasurer

SOCIETY MEMBERS (As of 1983)

Mr. Richard T. Arkwright, Mrs. George S. Avery, Mr. Robert M. Baylis, Mr. John T. Burnell, Mr. Herman L. Clark, Mrs. John B. Daniels, Mrs. Dwight Demeritt, Mrs. Edmond T. Drewsen, Mr. William Ehrman* Mr. William K. Elliot, Mr. Andrew V. Fellingham, Mr. Arthur E. Flynn*, Mr. Gerard A. Gilbride, Mrs. Gerard A. Gilbride, Mrs. George E. Gosnell, Mrs. R. Whitney Gosnell* , Mrs. Dorothy P. Heindell, Dr. George L. Hogben, Mr. W. Wilson Holden*, Mrs. William E. Horwill, Mr. Charles E. Inniss*, Mrs. Remsen Johnson Jr., Mr. Edward A. Jones* Mrs. John J. Klobassa , Mr. Alfred A. Lama, Sister Mary Logan* Mr. Hamilton M. Love, Dr. Edwin P. Maynard, Jr.* Mrs. Waldo M. McKee, Mr. Theodore B. Meyerstein , Mrs. Harry L. Mirick, Mr. George M. Onken* Mr. Marshall Schwarz, Dr. Walter R. Stankewick, Mrs. Eustace L. Taylor, The Hon. William C. Thompson, Miss Marguerite S. Vollmar, Miss Ruth Wallace, Mrs. Francis E. Walton, Mrs. John Jay Wittmer

*Member, Board of Directors

18

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

LIFE

MEMBERS

Mrs.

Wendel P. Colton, Jr., Mrs.Rernsen

Johnson, Jr., Miss Marguerite S.Vollmar

HONORARY

MEMBERS

Mrs.

Russell T. Bailey, Mrs. Harry L. Mirick, Mrs.

Waldo M. McKee, Miss Marguerite S. Vollmer

EXECUTIVE STAFF

Mrs.

Betty C. Jones, Executive Director

CONSULTANTS

Mr.

Edward P. Beach, Financial Consultant

DOUBLE

DIAMOND ANNIVERSARY

COMMITTEE:

Mr.

Jonathan A. Clayton, General Chairman;

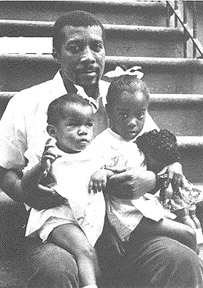

Fathers

are important, too.

Fathers

are important, too.

19

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Brookwood Child Care

Typography by Herb Field Studio Printing by Wintry Press Text by Frank Corwin

363 ADELPHI STREET BROOKLYN, NEW YORK 11238 TELEPHONE 212/783-2610

Founded May 17, 1833, as "The Orphan Asylum Society of the City of Brooklyn" Incorporated April 15, 1835, by an Act of the New York State Legislature